TIP4P model¶

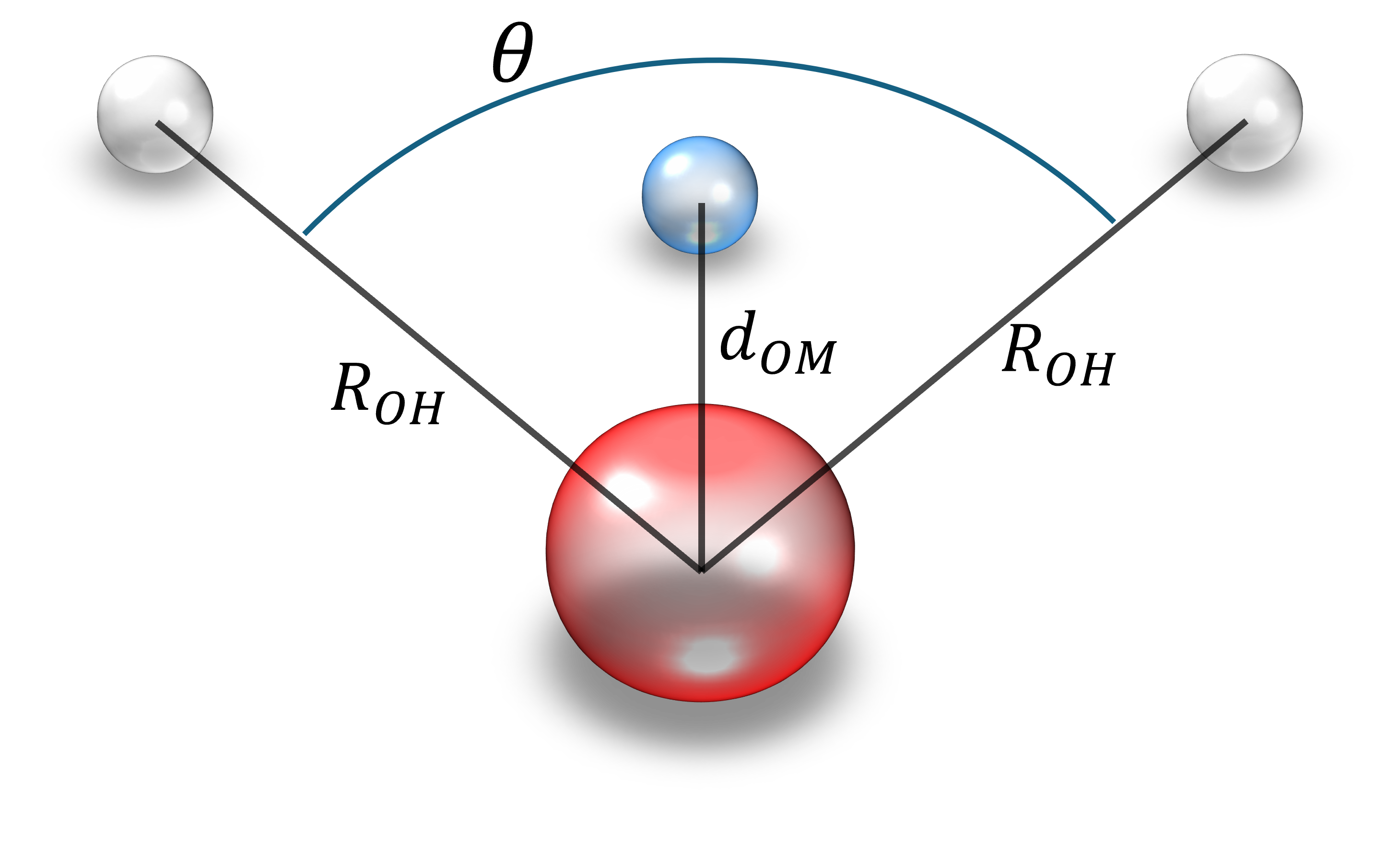

The TIP4P model is a classical, rigid water model designed to simulate the water molecular behaviour in MD and Monte Carlo simulations. Unlike simpler models, such as TIP3P or SPC, which use three interaction sites, the water molecule consists of four fixed interaction sites arranged as a rigid body in the TIP4P model:

- Two hydrogen atoms, each with a positive partial charge q_H.

- One oxygen atom, which participates in Lennard-Jones interactions but carries no charge.

- A massless dummy site (called the M site) located slightly offset, d_OM, from the oxygen atom along the bisector of the H-O-H angle. The negative partial charge of the molecule, q_M, is assigned to this M site.

This fixed geometry, maintained through rigid constraints, allows efficient simulations with larger time steps. More importantly, the placement of the negative charge at the M site enhances the electrostatic representation, particularly improving the dipole and quadrupole moments of the water molecule.

Among its variants, TIP4P/2005 [3] is particularly well-regarded for accurately key structural and thermodynamic properties of water. While slightly more computationally demanding than three-site model, TIP4P/2005 offers a strong balance between physical realism and performance.

Therefore, we set parameters for moleculary geometry and Lennard-Jones potential following TIP4P/2005.

Exercise:

- Set following parameters:

OO_SIGMA: The sigma for Lennard-Jones interactions between oxygenOO_EPSILON: The (dimensionless) interaction strength epsilon for Lennard-Jones interactions between oxygenR_OH: The distance between oxygen and hydrogentheta: H-O-H angled_OM: The distance between oxygen and the M siteq_H: a partial charge for hydrogenq_M: a partial charge for the M site

Hint:

- All parameters are wrriten in the paper [3].