Discretization¶

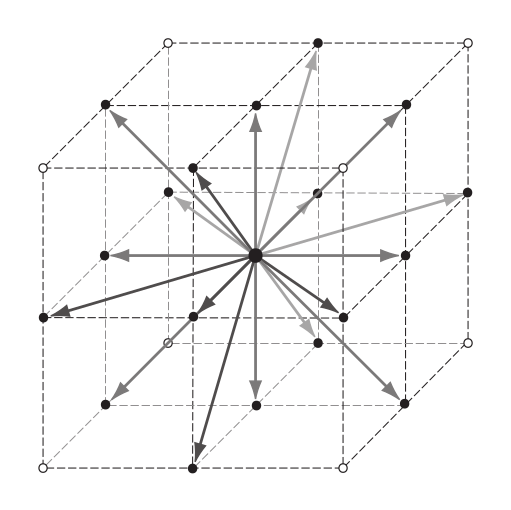

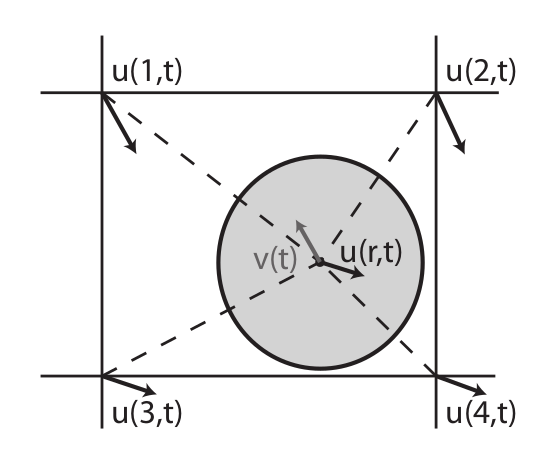

The LBM discretizes the Boltzmann equation not only in real space (the lattice!) and time, but also the velocity space is discretized. A surprisingly small number of velocities, usually 19 in 3D, is sufficient to describe incompressible, viscous flow correctly. Mostly we will refer to the three-dimensional model with a discrete set of 19 velocities, which is conventionally called D3Q19. These velocities, $\vec{c_i}$ , are chosen such that they correspond to the movement from one lattice node to another in one time step. A two step scheme is used to transport information through the system. In the streaming step the particles (in terms of populations) are transported to the cell where the corresponding velocity points to. In the collision step, the distribution functions in each cell are relaxed towards the local thermodynamic equilibrium. This will be described in more detail below.

The hydrodynamic fields, the density $\rho$, the fluid momentum density $\vec{j}$ and the pressure tensor $\Pi$ can be calculated straightforwardly from the populations. They correspond to the moments of the distribution function:

\begin{align*} \rho &= \sum_i f_i \\ \vec{j} = \rho \vec{u} &= \sum_i f_i \vec{c_i} \\ \Pi^{\alpha \beta} &= \sum_i f_i \vec{c_i}^{\alpha}\vec{c_i}^{\beta} \end{align*}Here the Greek indices denotes the cartesian axis and the Latin indices indicate the number in the discrete velocity set. Note that the pressure tensor is symmetric. It is easy to see that these equations are linear transformations of the $f_i$ and that they carry the most important information. They are 10 independent variables, but this is not enough to store the full information of 19 populations. Therefore 9 additional quantities are introduced. Together they form a different basis set of the 19-dimensional population space, the modes space and the modes are denoted by $m_i$. The 9 extra modes are referred to as kinetic modes or ghost modes. It is possible to explicitly write down the base transformation matrix, and its inverse and in the ESPResSo LBM implementation this basis transformation is made for every cell in every LBM step.